Peter literally denied knowing Jesus three times in front of a crowd, but Jesus still made him the leader of the early church. That should inform our understanding of what forgiveness and grace really mean.

But let's back up and talk about what faith used to cost people.

Becoming a Christian before Constantine legalized it in 313 CE wasn't like checking a box on a survey or walking an aisle at summer camp. It was often literally life or death. The Romans usually didn't see Christians as a harmless religious minority—they saw them as enemies of the state, traitors who refused to participate in the civic duty of emperor worship.

This is why the early church kept the Eucharist a secret from new converts until they were baptized at Easter. They called these learners "catechumens," and they weren't allowed to witness the most sacred parts of Christian worship because the church couldn't risk spies infiltrating their services. Getting caught meant complete economic ruin, torture, or death. Your neighbors could turn you in. Your business partners could shun you. Your family could disown you.

Christianity wasn't a personal relationship with Jesus that you could keep private while living a completely normal Roman life. It was a radical reorientation of your entire existence that put you at odds with the empire itself.

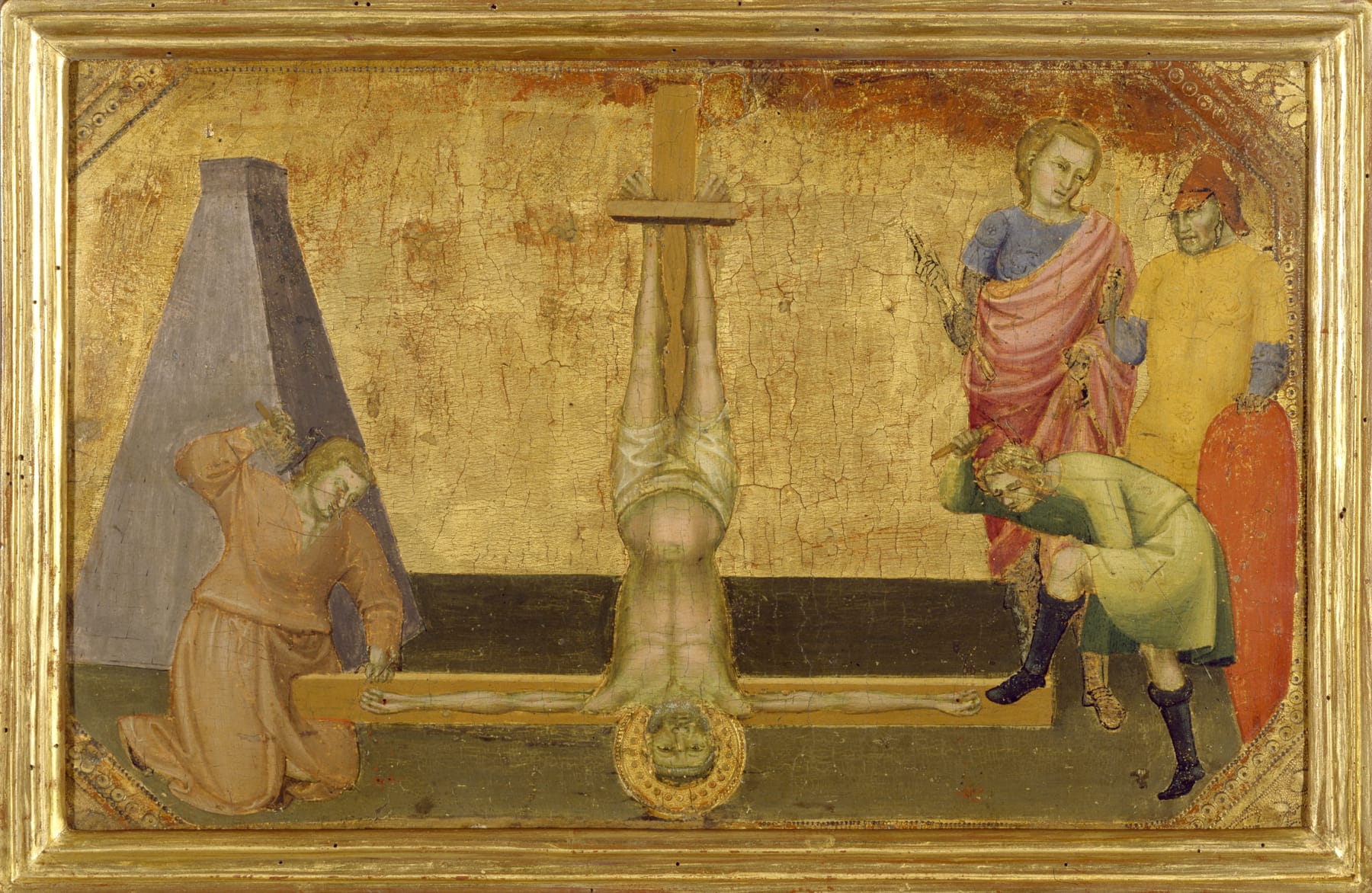

So when persecution hit hard—and it did, repeatedly, under emperors like Nero, Decius, and Diocletian—some Christians cracked under pressure. They'd burn incense to the emperor, deny their faith publicly, hand over their scriptures to be burned, or perform whatever ritual sacrifice was required to prove their loyalty to Rome. The church called them the "lapsi," from the Latin meaning "the fallen ones" or "those who have slipped."

And honestly? I get it. Imagine watching your friends tortured to death, knowing you're next, and some Roman official offers you a way out: "Just burn a little incense. Just say the words. Nobody has to die today."

But when persecution died down and these people wanted to return to the church, it caused absolutely massive drama. The Christian community basically split into two camps:

The Rigorists said absolutely not. These people had abandoned the faith when it mattered most. They'd watched their own family members die while they chose to save their own skin. They'd betrayed everything the church stood for. Once you deny Christ, you're done. No take-backs.

The Laxists argued for forgiveness and some form of penance. Yes, what the lapsi did was wrong, but isn't forgiveness at the heart of the gospel? Shouldn't there be a path back to the community?

The rigorists had a point. These weren't people who had simply doubted in private or struggled with their faith quietly. They had publicly rejected Christianity when the stakes were highest, when their communities needed solidarity most.

But Peter, the guy Jesus literally called "the rock" upon which he'd build his church, had done the exact same thing. When Jesus was arrested, Peter didn't just distance himself quietly—he straight-up pretended he didn't know Jesus. Not once, not twice, but three times. In public. While Jesus was being tortured.

Luke 22 tells us that after Peter's third denial, "the Lord turned and looked at Peter." Can you imagine that moment? The betrayal, the shame, the realization of what he'd just done?

All the male disciples scattered like leaves when things got dangerous. Only the women—Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, Joanna, and the others—stayed for the crucifixion. The men who would become the foundation of the early church all abandoned Jesus when it counted.

Yet Jesus didn't write them off. He didn't establish a new leadership structure or find more reliable apostles. He restored Peter specifically, asking him three times to "feed my sheep"—once for each denial.

I get having moments where faith feels negotiable (though maybe not with the same high stakes). When I was sixteen at youth group, I literally told God I would give up the faith and burn in hell if it meant Megan Ramundo would talk to me. I'm not sure why God would want to broker that particular deal, but I was sixteen and very confused.

My point is that I think many of us have our moments of cosmic bargaining and faithless desperation. The difference is that my teenage theological confusion didn't happen under threat of torture. I wasn't facing the choice between faith and death. I was just pubescent and awkward.

When Faith Costs Nothing

Now let me tell you something about our culture: we live in a place where being Christian is so mainstream that it's basically cultural wallpaper. You can slap a Jesus fish on your car, attend Easter service, and call it a day. Politicians invoke Jesus to get votes. Christian movies make millions at the box office. You can find Bible verse decor at Target.

Faith has been made so safe and comfortable that some have forgotten what it cost our spiritual ancestors. They lost everything—their lives, their families, their livelihoods—for this faith we often treat like a lifestyle choice or political affiliation.

When faith costs nothing, it's easy to take lightly. When there's no sacrifice involved, no real transformation required, no countercultural commitment demanded, then "losing your faith" becomes as casual as changing your Netflix subscription.

The flip side of that coin is that some churches today still operate like those ancient rigorists, insisting that once you leave the faith, you can never truly come back. Once you apostatize, you're done. Simultaneously they can promote once saved, always saved—but also, once fallen, always fallen. They'll speak of "backsliders" and "prodigal sons" who might return, but there's always that underlying suspicion that real Christians wouldn't actually walk away. So those that do walk away must not have been real Christians in the first place.

This creates its own form of spiritual abuse, where people are afraid to voice doubts, ask hard questions, or admit when their faith is struggling because the cost of honesty might be permanent exclusion from their community.

But Jesus clearly disagreed with this approach when it came to Peter. The guy who denied him publicly became the leader of the apostles. The disciples who abandoned him became the foundation of the early church.

The Messy Middle

The truth is, faith isn't a straight line. It's messy, it's complicated, and sometimes we all chicken out in various ways. Maybe you've walked away from faith entirely because the version you were handed was toxic or harmful. Maybe you've cursed God out during your darkest moments. Maybe you've denied what you believed when it wasn't convenient or cool.

Jesus didn't write Peter off for his doubt and fear, and I don't think he's writing you off either.

But here's the challenge that comes with grace: maybe it's time we took our faith as seriously as those early Christians did. Not the life-or-death part necessarily, but the radical commitment part. (Although faith still is life-or-death in many places in the world). The part where following Jesus actually changes how we live, not just what we do with our free time on Sundays.

What would your faith look like if it actually cost you something? What if it meant choosing economic disadvantage to live ethically? What if it meant standing up for marginalized people even when it makes you unpopular? What if it meant genuine forgiveness instead of just posting inspirational quotes about grace?

What if being a Christian meant something more than cultural identity or political tribe membership?

The Invitation Back

If you've walked away—whether from toxic Christianity, spiritual abuse, or just the slow drift of apathy—there's something beautiful about Peter's story. His failure wasn't the end. His denial didn't disqualify him from leadership. His moment of cowardice didn't define his entire relationship with Jesus.

The early church ultimately found a middle way between the rigorists and the laxists. They developed practices of confession, penance, and restoration that acknowledged the seriousness of abandoning the faith while still leaving the door open for return. It wasn't easy, and it wasn't cheap grace, but it was possible.

Maybe that's what we need today: practices that take faith seriously without making it impossible to return when we mess up. Communities that cost us something without becoming abusive. Theology that acknowledges both the weight of commitment and the reality of human failure.

After all, if Jesus could trust the guy who denied him three times to lead his church, maybe there's hope for the rest of us who've chickened out in our own ways.

The question isn't whether you've been faithful enough. The question is whether you're ready to take faith seriously enough that it actually changes something about how you live.

And if you've been away, the question is whether you're ready to come back—not to the toxic parts of Christianity, but to the radical love that made people willing to die for it.

Just like Peter did.

Discussion