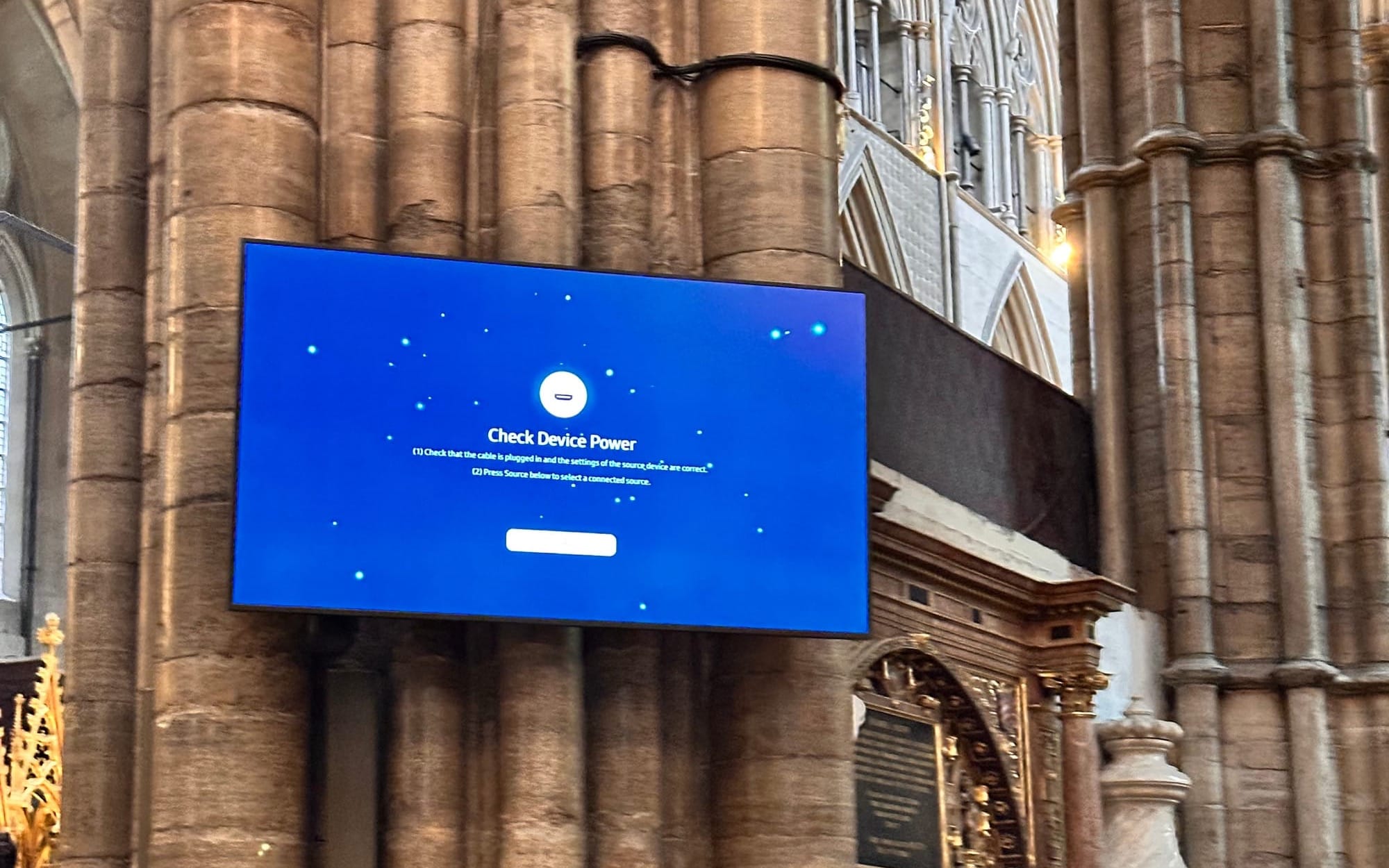

One Sunday, the slides didn't work. Or, more accurately, there was no one to run the slides.

I watched from the back as the congregation fumbled for their phones, squinting at tiny screens to find the second verse to "How Great Thou Art." A few people just sang from memory, their voices carrying the melody while others hummed along uncertainly. It wasn't polished. It wasn't seamless. It was beautifully, messily human.

And it was exactly what needed to happen.

A Theology of Imperfection

"Let there be gaps" has become one of my core ministry philosophies—a deliberate choice to prioritize people over performance, souls over systems. It can sound nearly heretical in a church culture obsessed with ✨excellence✨, where we've bought into the lie that God's love somehow depends on our ability to deliver a flawless Sunday morning experience.

But ministry is too precious, too holy, too sacred to treat volunteers like cannon fodder. As my old boss Pastor John Messer used to say, "We don't throw people into the breach—and yet that's exactly what happens when we prioritize institutional perfection over human dignity. We create a system where the same faithful few run slides every single week, make coffee every single Sunday, staff the nursery until they're running on nothing but fumes and resentment.

We might tell ourselves it's for the good of the congregation. We convince ourselves that gaps would hurt people's experience. But what we're really doing is participating in a consumerist theology that says the church exists to be purveyors spiritual goods and services rather than to form a community of mutual care and shared responsibility.

The Crisis of False Abundance

Here's what I've learned: when the same two people handle the slides every week without fail, the congregation assumes everything is fine. They hear announcements about needing volunteers, but their eyes tell them a different story. The slides are up. The coffee is hot. The nursery is staffed. Clearly, they don't really need help.

This is where some HBR change management wisdom intersects with Gospel truth—sometimes you have to let the status quo reveal its own unsustainability. When people show up and there are no slides, when the coffee station sits empty, when childcare isn't available because we're giving our volunteers the sabbath they deserve, suddenly the invisible labor becomes visible. The need becomes real.

Sometimes you have to let the status quo reveal its own unsustainability.

I'm not talking about manufactured crises or manipulatively withholding care. I'm talking about an honest acknowledgment that we cannot and should not expect a handful of people to carry the entire burden of communal worship. When gaps appear, they create space for new voices, new hands, new hearts to join the work.

Beyond the Consumer Church

The resistance to this philosophy reveals how deeply we've internalized a consumer model of faith. We've divided our communities into producers and consumers, where a dedicated few work tirelessly to provide a five-star spiritual experience for everyone else. It's Burger King theology. Have it your way—fast, convenient, consistent, and utterly devoid of the messy beauty of authentic community.

But the early church looked nothing like this. In those house churches scattered across the Roman Empire, everyone contributed something. Everyone brought their gifts, their resources, their presence to the common table. The community's wellbeing was a shared responsibility, not the burden of a pastoral staff and a small group (usually 20% of the congregation) of the loyal volunteers.

This is koinonia—the kind of fellowship that says we are all producers and consumers simultaneously. We all contribute to and benefit from the community's life together. It's a radically different vision from the church-as-vendor model that has infected so much of American Christianity.

The Art of Sacred Disruption

Letting gaps show can be an (albeit risky) act of prophetic imagination. It disrupts the fantasy that churches run on pastoral magic and volunteer martyrdom. It forces us to confront the question: what are we actually here for?

Maybe folks aren't coming for your artisanal coffee or your perfectly timed slide transitions. Maybe they're coming for something deeper—connection, meaning, a place to wrestle with the holy mysteries. When you strip away the non-essentials— what my Old Testament professor called the "butt-naked essentialism"—you discover what actually matters to your community.

I've seen churches panic about nursery coverage, only to discover that families are (occasionally!) happy to worship together, children included. I've watched congregations survive electricity failures and realize that singing together, voices mingling without the crutch of perfect technology, actually created more intimacy than any polished presentation ever could.

Sabbath for the Servants

At its foundation, this philosophy is about extending sabbath rest to those who serve. It's recognizing that everyone—including your most dedicated volunteers—deserves to sit in the pew, to receive rather than give, to be ministered to rather than always ministering.

If I as the pastor refuse to let the gaps show, I'm essentially saying that the comfort of the many matters more than the wellbeing of the few who serve. I'm prioritizing institutional appearance over individuals. I'm perpetuating a system where faithfulness is rewarded with endless obligation. Ew.

But what if I trusted that God's work doesn't depend on my ability to maintain perfect systems? What if I believed that the Spirit moves just as powerfully—maybe more powerfully—in the spaces between our carefully planned programs?

The Beautiful Breakdown

That Sunday when there was no one behind the iMac keyboard, something beautiful happened in the breakdown. People looked up from their phones and made eye contact. They listened more carefully to the words they were singing. They helped each other find the page numbers in hymnals we hadn't used in months.

And by Tuesday, three people had volunteered to join the tech team.

The gap had done its work—not through manipulation or manufactured crisis, but through honest acknowledgment of our limitations and trust in the community's capacity to respond. It was a tinsy-tiny resurrection, the kind that happens when we stop trying to control every outcome and start believing in the church's ability to be the church.

What gaps might your community need to see? What would happen if you trusted your congregation with the truth about your needs rather than maintaining the illusion of perfect systems? Sometimes the most faithful thing we can do is admit we can't do it all—and create space for others to discover their own calling in the work of love.

Discussion