As a pastor, I love watching people approach our communion table—some eager, some hesitant, some with tears already forming. Over the years, I've been told by congregants many reasons why another church had denied them Communion:

- They were divorced

- They weren't baptized in the right denomination

- They were LGBTQ+

- They disagreed on some theological point

So when people are told, each and every Sunday, that there is nothing barring them from the table, it's no wonder that emotions come to the surface.

The reasons to deny someone break my heart and fill me with something close to righteous anger. Somewhere along the way, the turned Jesus's radical act of hospitality into a spiritual membership card.

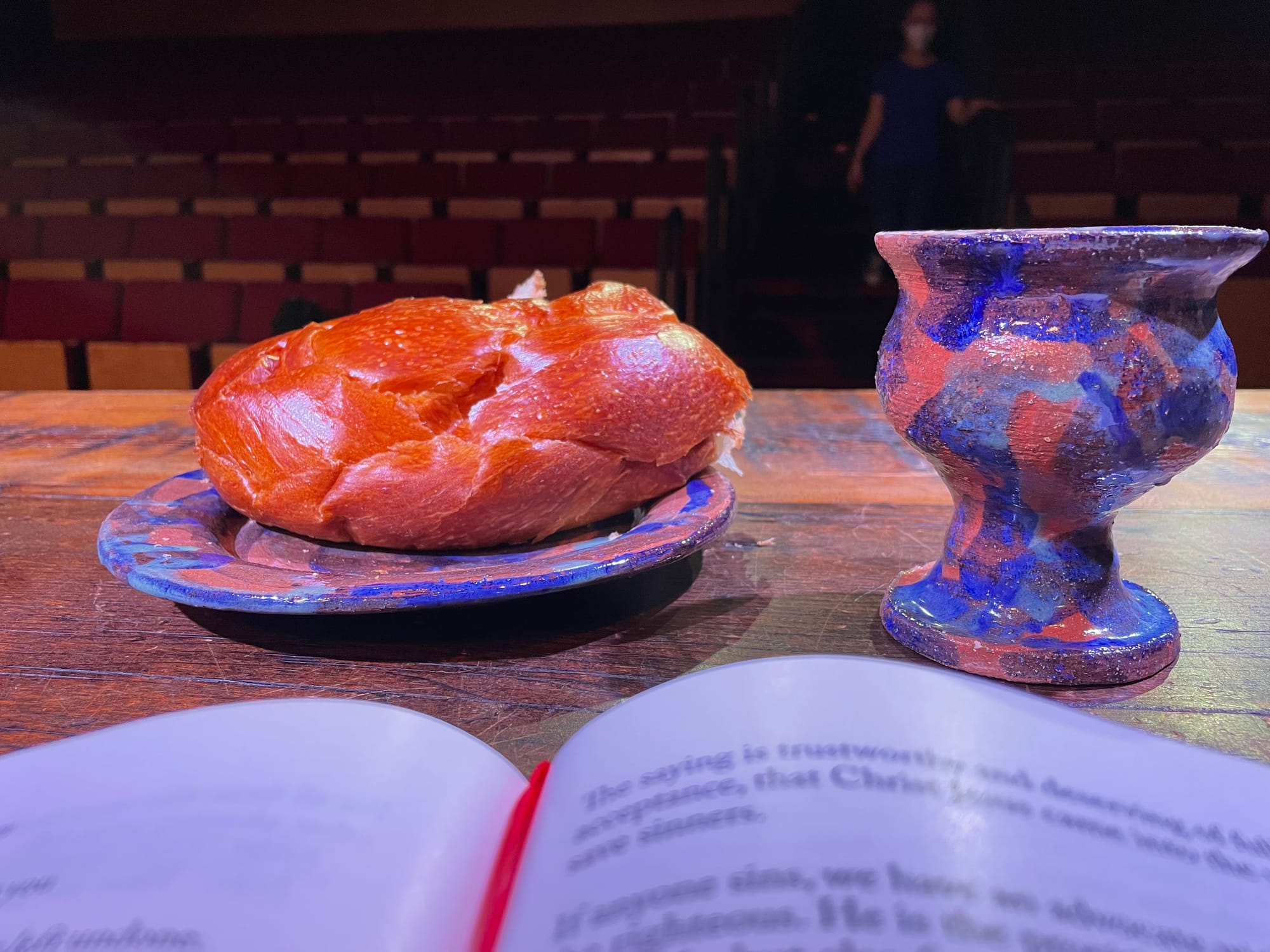

The Meal That Started It All

Christianity's oldest continuous ritual isn't baptism (which was originally a Jewish rite)—it's the Lord's Supper. Before there were creeds or denominations or arguments about drum volume, there was bread broken and wine poured. Jesus took the Passover meal, that ancient celebration of liberation from Egypt, and made it about liberation from everything that tries to separate us from God and from each other.

As N. T. Wright puts it, "When Jesus wanted to explain salvation, he didn't give us a sermon; he gave us a meal."

The word "Eucharist" comes from the Greek eucharisteo—to give thanks. It's fundamentally about gratitude, about recognizing the abundance of God's provision. But over the centuries, we've managed to transform thanksgiving into gatekeeping, grace into exclusion, invitation into interrogation.

Before the Protestant Reformation, the Eucharist was the center and focus of Christian worship. You didn't go to church to hear a forty-five-minute sermon from a trained rhetorician. You went to experience the sacrament of the Eucharist, to taste and see that the Lord is good—literally. The table was the center, not the pulpit.

It was John Calvin, primarily, who changed that emphasis, shifting focus from sacrament to Scripture, from mystery to explanation. That shift did gave us brilliant biblical scholarship and vibrant preaching, yes, but it also opened the door to personality-driven, celebrity pastor culture. When preaching becomes the main event, suddenly the quality of your Sunday experience depends on whether the guy with the microphone is having a good day.

But before then (and it continues in many mainline churches today) the ritual of communion had been the primary center—the table was where heaven and earth mingled, where the ordinary became sacred, where community was both created and sustained.

What Actually Happens When We Eat and Drink?

After two thousand years, Christians still can't agree on what on earth actually happens during communion. Unsurprisingly for my readers, I find that disagreement beautiful rather than frustrating. Mystery has room for wonder; certainty tends to close doors.

Roman Catholics believe in transubstantiation—the bread and wine literally become the body and blood of Jesus. Medieval philosophers got wonderfully nerdy about this, distinguishing between "substance" (the underlying reality) and "accidents" (what your senses perceive). So while the communion elements still look and taste like bread and wine, their essential reality has been transformed. You're eating what appears to be a wafer but is actually Christ himself.

Putting aside the typical Protestant/Catholic debates about this, there's something profoundly incarnational about this view. God doesn't just show up spiritually, but becomes as real and present as anything you can hold in your hands. The Protestant critique is usually that it the Catholic mass is no better than animal sacrifice, as if Jesus is being re-sacrificed every time mass is celebrated. Catholics would push back, however. They're not re-sacrificing Christ; they're participating in the once-for-all provision of his sacrifice that exists outside normal time and space.

Lutherans developed consubstantiation—the body and blood are present with the bread and wine rather than replacing them. It's communion elements plus Jesus, not communion elements becoming Jesus. Less philosophically demanding, maybe, but still maintaining that something real and mystical is happening beyond just remembering.

Many Protestants landed on memorialism—communion is solely symbolic, a way of remembering, memorializing Christ's death. "This do in remembrance of me." The bread represents the body, the wine represents the blood, but nothing supernatural is occurring. It's a memorial service with snacks! This view emerged partly from a desire to democratize the sacred (anyone can understand symbols) and partly from suspicion of anything that smacked of "Catholic magic."

Then there's Real Presence—the view I hold and that many Episcopalians and United Methodists embrace. In this view, Christ is genuinely present in the elements, but we're not going to pretend we can explain exactly how. John Wesley called communion a "means of grace"—a tangible way of experiencing the invisible reality of God's love. Something sacramental is happening; something mystical is occurring; something beyond mere memory is taking place. As the Celtics would put it, the communion table is a "thin place" between heaven and earth.

I believe this because communion has never felt like just remembering to me. When I tear the bread and say "Jim, this is the body of Christ, broken for you," when I lift the cup and declare "Imani, this the blood of Christ, shed for you," there's a weight to those words, a presence in that moment that feels as real as anything I've ever experienced. Call it psychology, call it the power of ritual, call it God—I know something is happening beyond my ability to explain or control.

The Problem of the Fenced Table

But who gets to experience whatever this mysterious, beautiful thing is? Ah, now we get to the part that makes my blood pressure rise.

"Fencing the table" means deciding who's allowed to participate in communion and who has to sit there awkwardly while everyone else gets to eat. Some churches fence it narrowly—only members of their specific denomination. Others fence it broadly—anyone who's been baptized and professes faith in Jesus. Still others fence it selectively—you have to pass some kind of theological purity test.

Early churches did practice closed communion, but context matters. For the first three centuries, being known as a Christian could cost you your job, your social standing, potentially your life. Church membership meant something when it might mean martyrdom. The six to twelve months of training before baptism wasn't about keeping people out; it was about making sure people understood what they were signing up for.

But we're not living under Roman persecution anymore (despite what some American Christians would have you believe). We're living in a country where being Christian is still largely socially advantageous, where churches compete for members like businesses compete for customers. The context that made closed communion protective has evaporated.

And if we actually look at Jesus's practice—which should probably matter more than later church tradition—he doesn't fence the table.

The Radical Inclusivity of Jesus

At the Last Supper, Jesus offers bread and wine to Peter, who he knows will deny him before the rooster crows. He offers it to Judas, who he knows will betray him for thirty pieces of silver. He offers it to all the disciples, who he knows will abandon him when things get dangerous in Gethsemane. If Jesus was willing to share this sacred meal with people who would literally sell him out and run away, what does that say about our requirements for "worthiness"?

Throughout the Gospels, there's a consistent pattern of Jesus breaking bread with all sorts of people—feeding the five thousand who just showed up hungry, eating with tax collectors and sinners who religious folks thought were beyond redemption, sharing meals with disciples who still didn't understand half of what he was teaching.

Look at the language used to describe the feeding miracles: "Jesus took the bread, gave thanks, and broke it." Sound familiar? It's almost identical to the communion language. Those weren't communion services, but they were communion-like—moments where the abundance of God's provision was made tangible, where everyone was welcomed to the table regardless of their spiritual resumé.

After his resurrection, Jesus reveals himself to the disciples on the road to Emmaus by breaking bread with them. These weren't the inner circle of twelve; these were disciples who had given up, who were literally walking away from Jerusalem in despair. And yet Jesus sits at their table, breaks bread with them, makes himself known in the sharing of the meal.

The Misreading That Keeps People Away

Churches usually justify excluding people by pointing to Paul's warning in 1 Corinthians 11 about eating and drinking "unworthily." I've heard this passage weaponized many times. A pastor would spend ten minutes warning us about divine punishment awaiting anyone who took communion without proper reverence, proper understanding, proper spiritual preparation. I watched adults around me examine their souls like they were cramming for the most important test of their lives.

But Paul isn't talking about individual spiritual readiness. He's not threatening divine lightning strikes for people who haven't dotted every theological i and crossed every doctrinal t.

The context is crystal clear if you actually read the whole passage instead of just proof-texting verse 27. (I write more about this here) Paul is addressing a church where rich members were showing up early to communion, eating all the good food, drinking all the wine, and leaving scraps for the poor members who couldn't get off work until later. The wealthy were turning the Lord's Supper into a power display, a way of flaunting their privilege while humiliating people with less.

"Don't you have homes to eat and drink in?" Paul asks the rich members. "Or do you despise the church of God by humiliating those who have nothing?"

Paul's warning about eating "unworthily" isn't about theological purity—it's about economic justice. He's saying that if you turn communion into a way of showing off your wealth while ignoring the hungry people sitting next to you, you're missing the entire point. The "body of Christ" you're dishonoring isn't just the bread and wine; it's the actual body of Christ, the church itself, especially the most vulnerable members.

When Paul says some people have become "weak and sick and some have even died," he's not describing divine punishment for communion mistakes. He's pointing out that when the wealthy hoard food while the poor go hungry, people literally suffer and die. Getting communion wrong isn't a liturgical error—it's a justice issue with life-and-death consequences.

Our Practice: Scandalously Open

So at The Table Church, we practice open communion. When we gather around the table each Sunday, we say: "Anyone who seeks the grace of God is welcome at this table."

You don't have to be Christian. You don't have to be baptized. You don't have to have your theology figured out or your life cleaned up. You don't have to agree with everything we believe or promise to start tithing and coming to church regularly. The only requirement is wanting to be there—some hunger, some curiosity, some longing for connection with the divine.

This makes some people uncomfortable. I've had thoughtful, progressive Christians tell me there should be some boundaries, some requirements. What about communion with an ICE officer and an undocumented immigrant at the same table? What about someone whose very job involves harming the people we're called to protect?

I understand the discomfort. I wrestle with it myself. But my answer keeps coming back to Judas at the Last Supper. If Jesus was willing to share this meal with someone who would literally orchestrate his death, then I'm not sure I'm in a position to be more exclusive than Jesus was.

This doesn't mean communion is cheap grace or that all choices are equally valid. It means the table is a place of encounter, not judgment. It means we trust that God is big enough to work in hearts we might have written off. It means we'd rather err on the side of radical hospitality than cautious exclusion.

The table is a place of encounter, not judgment.

The Table That Changes Everything

Communion—at its best—isn't about individual piety or personal salvation. It's about recognizing that we are what we eat, that sharing the meal creates us as a people, that taking Christ into our bodies makes us the body of Christ in the world.

The early Christian phrase was "partakers of the divine nature"—slowly becoming like what we consume, gradually being divinized through encounter with the sacred. This is why I believe purely memorial views miss something crucial. If communion is just remembering, then we remain unchanged observers. But if something sacramental is happening, if we're actually being nourished by the presence of Christ, then we leave the table different than we came.

Every Sunday I watch people approach our communion table carrying their stories of exclusion, their histories of religious trauma, their questions about whether they belong anywhere. And every Sunday I get to say, "This is for you. You are welcome here. There is space at this table."

Sometimes I think about that woman who hadn't taken communion in fifteen years, about that college student who'd been told they weren't ready. I wonder how many people are sitting in church pews right now, watching other people eat while they're told to wait, told to prove themselves worthy, told they need to check more boxes before they can taste grace.

And I think about Jesus, breaking bread with betrayers and deniers and people who would run away when courage was required. Setting a table wide enough for anyone hungry enough to approach.

That's the real scandal of communion—not what happens to the bread and wine, but what happens to us when the table is exactly as wide as God's love.

Discussion