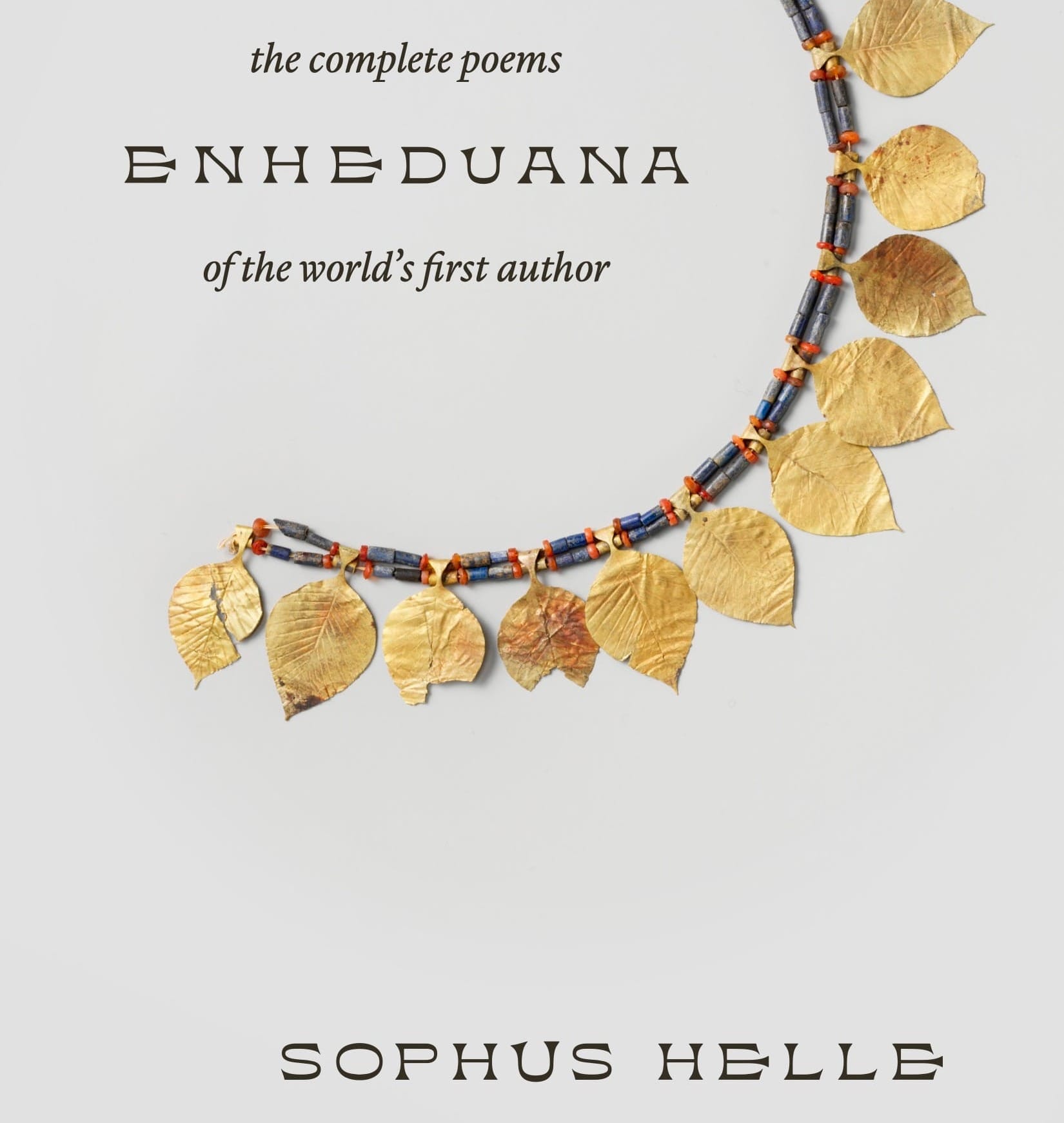

Author/Translator: Sophus Helle

Rating: 5/7 (Good, don’t go out of your way, but enjoyable

Date Finished: 2026-01-26

Part of my ongoing project has been reading the world's oldest literature. It helps me understand the world of the Bible, and ultimately, the world in general. Enheduana lived around 2300 BCE in Mesopotamia—making her writing older than Abraham by centuries.

Enheduana wasn't just an early author. She was the first named author in human history. We have older literature—fragments of hymns, prayers, administrative texts—but it's all anonymous or, if there is a name connected to it, it's incidental. With Enheduana, we know her name. We know her position (high priestess of the moon god Nanna in the city of Ur). We know she was studied. The reason her works survived is that students went to scribal schools and copied her poems as exercises. She wasn't just preserved—she was curriculum.

Here's a wild detail: for a while, scholars weren't sure if Enheduana actually existed or was a kind of literary persona, a figment of ancient imagination. Then archaeologists found a cylinder seal belonging to her hairdresser. Not Enheduana's own seal. Her hairdresser's. Which confirmed she was a real, historical figure—someone important enough that even her personal attendants had official seals.

It's strange to realize that the very concept of authorship is a human invention. Someone, at some point, decided it mattered who wrote something. And the first time that happened—the first time a name got attached to a body of work—it was a woman.

Helle's translation pairs Enheduana's hymns with substantial essays that contextualize both her poetry and her world. She was a devoted celebrant of Inana (the Sumerian goddess later syncretized with Ishtar). Her poems are intimate, passionate, and surprisingly confrontational. She writes of Inana the way a mystic might write of Christ—as lover, advocate, and overwhelming force.

The most fascinating insight for me was about images and personhood in ancient Mesopotamian thought. We tend to think of images as representations—a photograph captures someone, a portrait depicts them. But for the Sumerians, creating an image of a person didn't represent them. It extended them. An image gave someone further embodiment, further existence. It helped them be more fully. This has all sorts of implications for how we might read Genesis 1, where humanity is made as God's image. We're not merely representing God—we're extending God's presence into creation.

Also striking: the dramatic shift in how women were seen between the Old Assyrian and Old/Middle Babylonian periods. In Enheduana's time, women served as high priests. Goddesses held primacy in the pantheon. The first author in human history was a woman. But by the later Babylonian period, Enheduana had been forgotten, goddesses had been sidelined, and male gods dominated as creators and powers. Makes you wonder what gets lost when cultures "progress."

Discussion